Surgery, Gastroenterology and Oncology

|

Abstract

Background: In spite of a more efficient approach to upper digestive bleedings over the past three decades, acute oesophageal variceal bleeding remains a severe and deadly complication in the cirrhotic patient life, which marks a turning point in the evolution of their liver disease.

Aim and Objectives: To determine the frequency of duodenal ulcer (DU), as well as other clinical characteristics occurring after endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) of the esophagus, Subjects and methods; The current study was carried out on 240 subjects selected from the out patient's clinic of Internal Medicine Department of monofia University hospital and to Kafr El- Shiekh Liver Diseases Research Institute admitted to the internal department, divided into 2 groups; (Group 1): included 120 patients having esophageal varices and will treated with band ligation, (Group 2): included 120 patient having esophageal varices not receiving band ligation as a control group.

Result: There was statistical significant between control group and EVL group Regarding to esophageal varices grading, PHG grading and duodenal ulcers occurrence after 3 follow up.

Conclusion: EVL increased the frequency of DU in esophageal varices (EV) patients, which was related to the number of ligating bands employed during EVL, but was not related to Hp infection. EVL may also impact abnormalities in gastrointestinal peristalsis and the longevity of exposure of the duodenum to injurious substances. In addition, whether sclerotherapy, an alternative procedure, may also provoke a high incidence of DU and should be investigated in patients with EV.

Introduction

The dilated submucosal distal esophageal veins that join the portal and systemic circulations are known as esophageal varices. This is brought on by portal hypertension (most usually caused by cirrhosis), portal increased portal venous blood input and blood flow. The most typical Variceal rupture is a deadly side effect of cirrhosis; the severity of liver disease corresponds with the possibility of bleeding and the existence of varices (1-4). At present, the preferred treatment modality for attenuating EVr bleeding is endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) (5). Endoscopic variceal band ligation (EVL) is the endoscopic treatment of choice for oesophageal varices (EV) because it is more effective and safer than endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) (6).

Duodenal ulcer (DU) is one of the major gastro-intestinal disorders, which affects annually approximately 10–15% of the population worldwide (7). DU has been known for thousands of years (8). A significant proportion of patients with liver cirrhosis present with non-variceal upper GI bleeding, a major cause of which is peptic ulcer disease. Approximately 30-40 % of cirrhotic patients can present with a non-variceal cause of bleeding. Additionally, research has revealed that these patients are substantially more likely than the overall population to experience peptic ulcer haemorrhage (9).

Worldwide, the most common cause of upper GI bleeding is peptic ulcer disease followed by varices. Other causes encompass a variety of conditions ranging from esophagitis, gastritis, Mallory Weiss tear, malignancies, and portal hypertensive gastropathy (10). Therefore, our study aimed to determine the frequency of duodenal ulcer (DU), as well as other clinical characteristics occurring after endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) of the esophagus.

Patient and method

The current study was carried out on 240 subjects selected from the outpatients' clinic of the Internal Medicine Department of Monofia University Hospital and to Kafr El- Shiekh Liver Diseases Research Institute admitted to the internal department. during a period between Aug-2020 to June -2021. They were divided into two groups Group 1: 120 patients having esophageal varices and will be treated with band ligation. Group 2: 120 patients having esophageal varices not receiving band ligation as a control group.

Patients with severe gastric varices received tissue adhesive injection, without endoscopy follows up, without complete clinical data, without satisfactory duodenal observation due to the presence of blood, History or evidence of HCC and portal vein thrombosis on the base of ultrasonography and alpha-fetoprotein, and Any patient with a duodenal ulcer at first presentation were excluded from our study.

All patients in the present study were subjected to full history taking, clinical examination, and laboratory investigtions including Complete blood count (CBC), Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, AST, serum albumin, ALP, serum total bilirubin, PT, INR, blood urea, serum creatinine, HCV-antibody and HBV surface antigen by ELISA, HCV-RNA by PCR (quantitative): Serum HCV-RNA was measured using commercial real-time RT-PCR kits on an Applied Biosystems PRISM 7700 sequence detector (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA). All patients with chronic hepatitis C were determined to be HCV RNA positive (RNA loads >100 copies/ml = 100 IU/ml (2.0 log IU/ml) according to previous publications (Candiotti et al., 2004), Serum alpha-fetoprotein and analysis for H Pylori infection, Child Turcotte Pugh score was calculated for all patients and Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Statistical analysis

The data collected were tabulated & analyzed by SPSS (statistical package for the social science software) statistical package version 22 on IBM compatible computer. Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS (statistical package for social science) program version 13 for windows and all the analysis a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. data were examined using the student t-test, ANOVA test, Chi-square test, Mann-Whitney test, and Spearman correlation test. Multivariate analysis (MVA) is used for the analysis of data involving more than one type of measurement or observation. It may also mean solving problems where more than one dependent variable is analyzed simultaneously with other variables.

Results

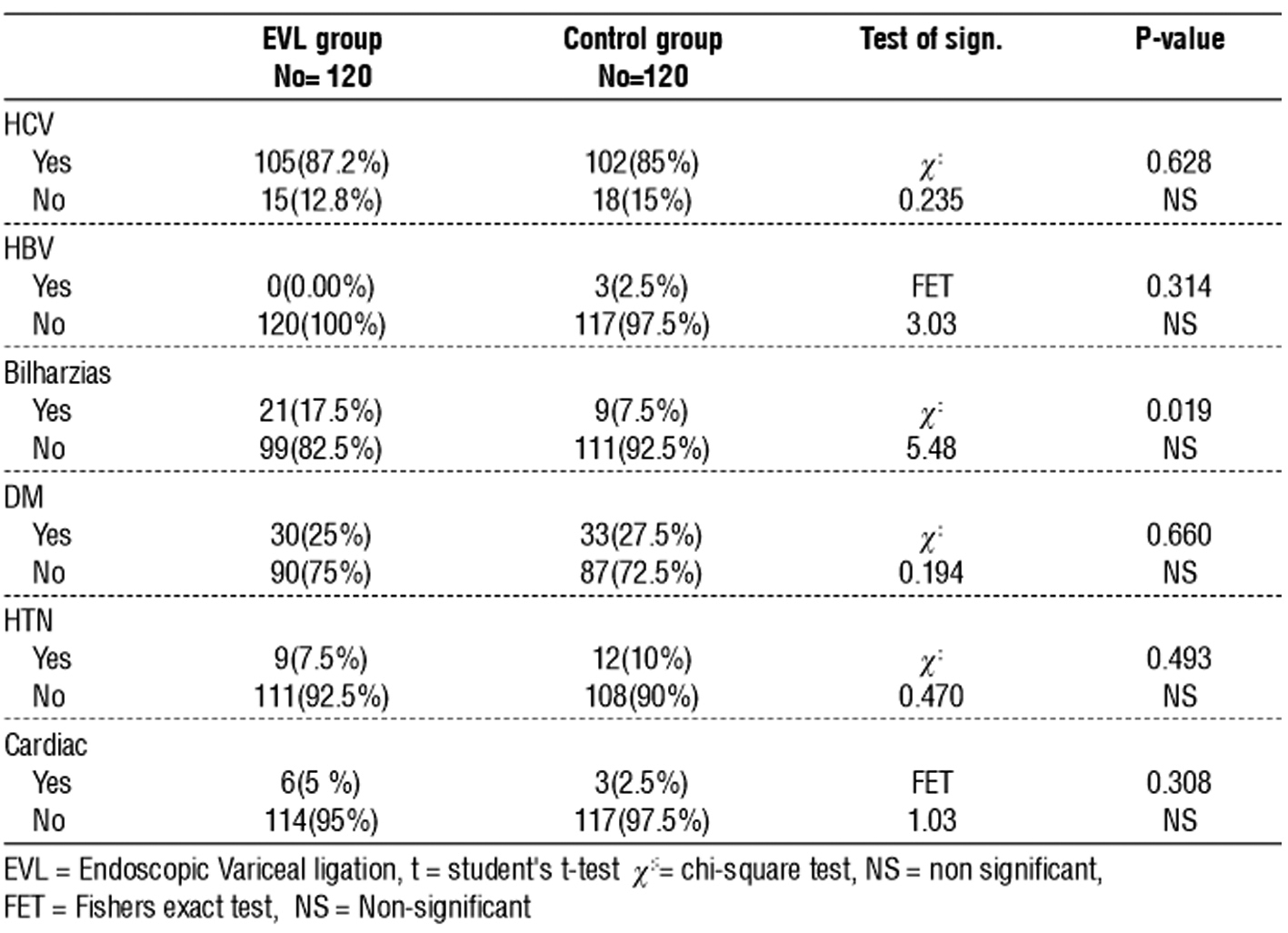

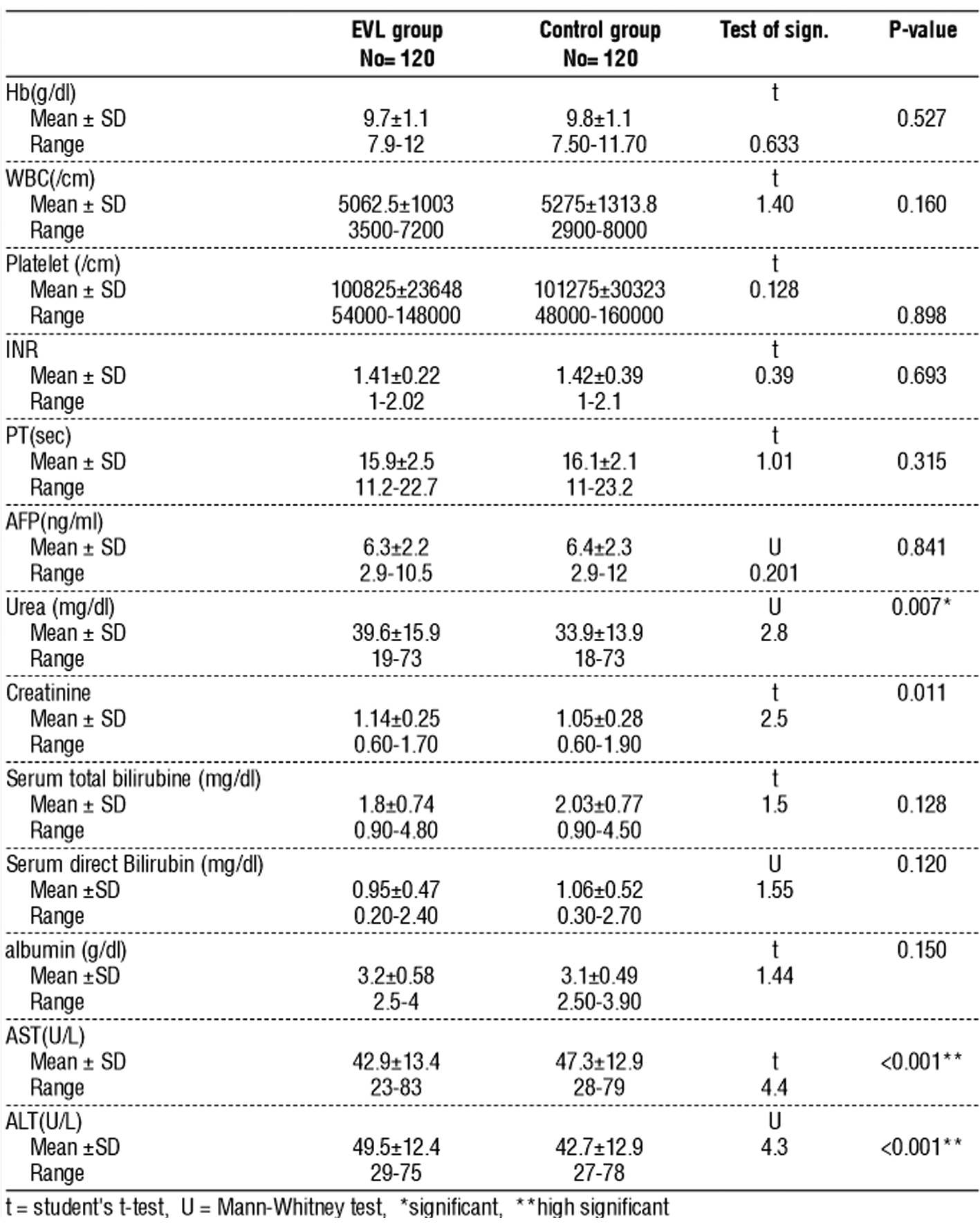

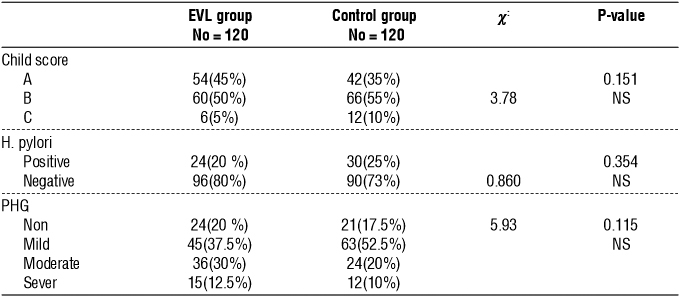

According to the medical history of the studied patients: There is no statistically significant difference between the control group and the esophageal ligation group (table 1). There were non-statistically significant differences between the two groups as regards each of Hb, WBCs, platelets, AFP, creatinine, and Serum total bilirubin, INR, PT, and Albumin while there were high statistically significant differences between the two groups as regards each of AST, ALT, and urea (table 2). There was a statistically insignificant difference between the control group and esophageal varices ligation group according to child score, H pylori infection, and PHG grading (table 3).

Table 1 - Medical history of studied patients (no=240)

Table 2 - Laboratory investigation of studied groups

Table 3 - Child score and H. pylori and endoscopic PHG finding among studied patients (no=240)

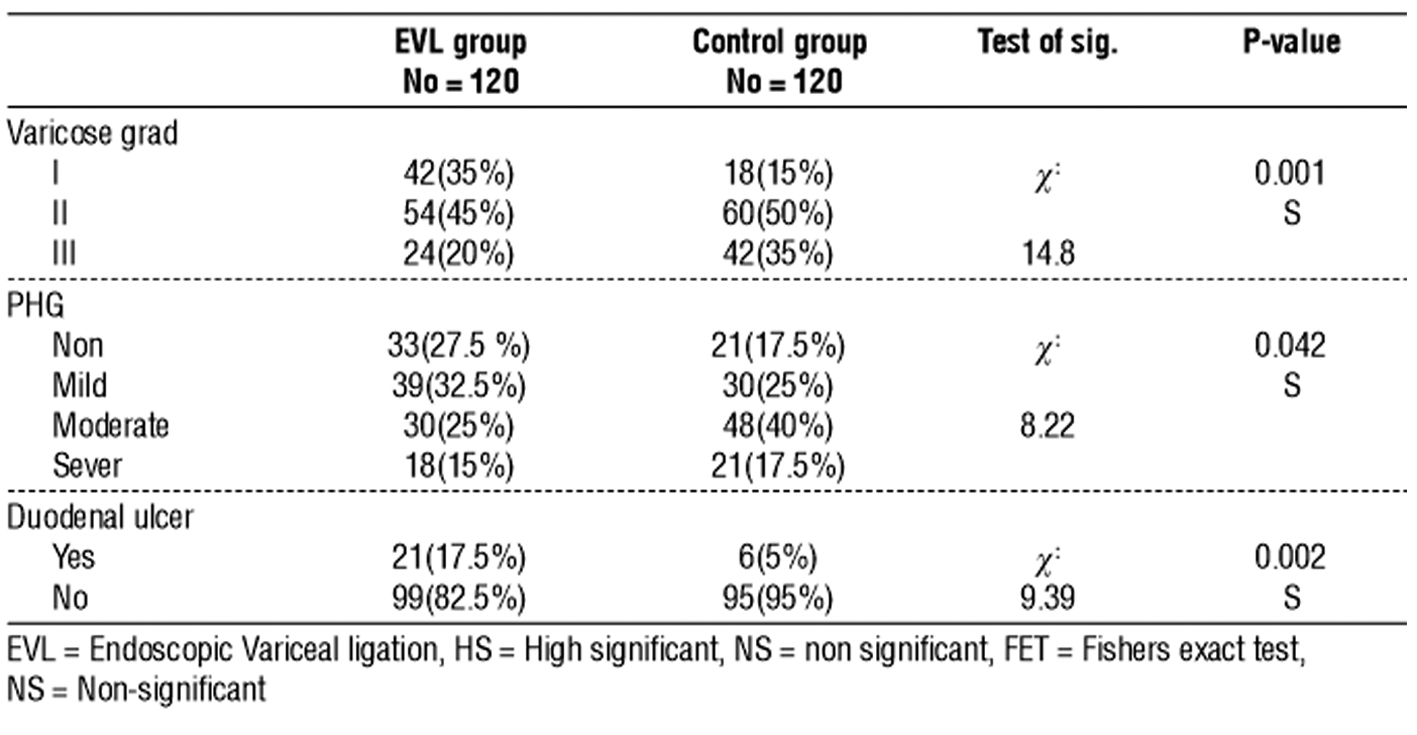

Table 4 - Endoscopic finding after 3 months among studied groups (no=240)

There was statistical significance between the control group and EVL group regarding esophageal varices grading, PHG grading, and duodenal ulcers occurrence after 3 follow up (table 4) a statistically

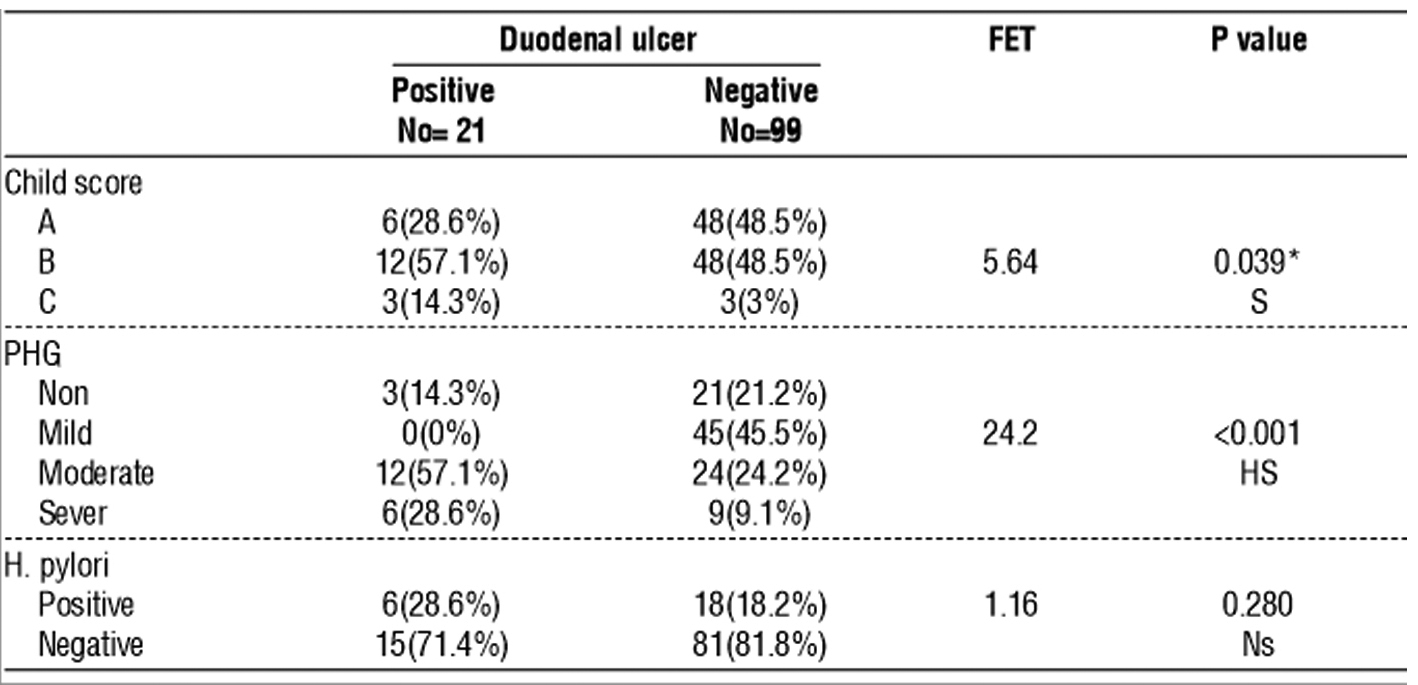

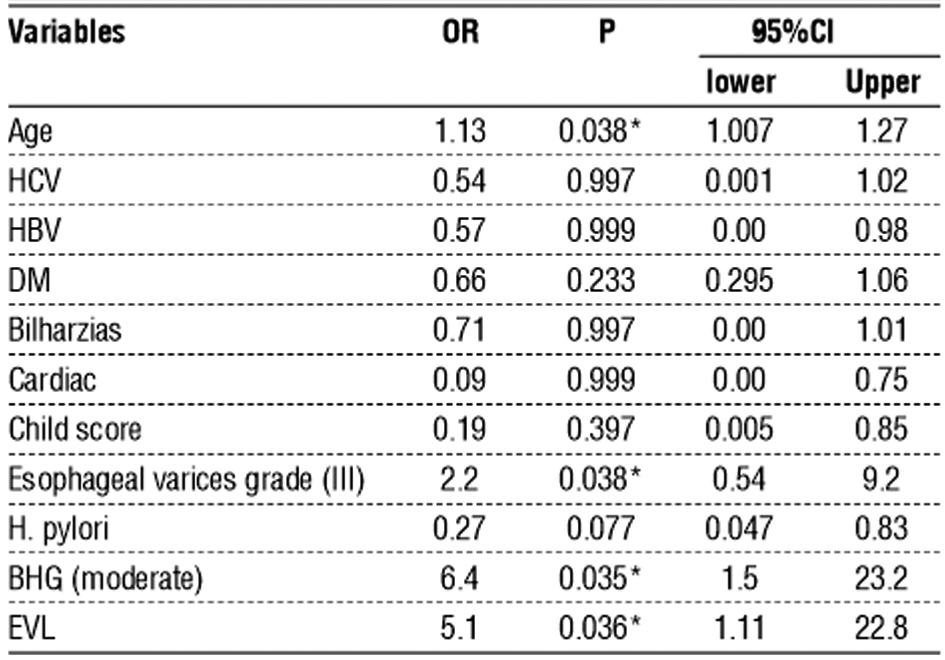

significant Relation between duodenal ulcer and child score, PHG grading, and H. pylori infection among EVL group (table 5). Esophageal varices grade (III), BHG (moderate), and EVL were independent predictors for duodenal ulcer (table 6).

Table 5 - Relation between duodenal ulcer and clinical data (pre-treatment) among EVL patients (no=120)

Table 6 - Multivariate logistic regression to detection the independent predictors for the presence of a duodenal ulcer

Discussion

Portal hypertension plays a crucial role in the transition from the preclinical to the clinical phase of cirrhosis: it is a contributive mechanism of ascites and encephalopathy, and a direct cause of variceal bleeding and bleeding-related death. Bleeding from ruptured oesophagogastric varices is the most severe complication of cirrhosis, and is the cause of death in about one-third of cirrhotic patients (11). The dilated sub-mucosal distal esophageal veins that join the portal and systemic circulations are known as esophageal varices. This occurs as a result of increased portal venous blood influx, portal hypertension, and resistance to portal blood flow. Variceal rupture is the most common fatal cirrhosis complication; the risk of bleeding and the existence of varices are correlated with the degree of liver disease (1).

Patients with esophageal variceal bleeding have higher rates of re-bleeding, complications, and death than patients with non-variceal bleeding such as ulcer bleeding. Traditional measures have included balloon tamponade, vasoconstrictors, and surgical intervention, but these measures did not significantly reduce the rate of re-bleeding, complications and improve survival (12). EVL is effective at controlling active bleeding from such varices with, reputedly, few undesirable side-effects. There are, however, several possible undesirable complications associated with EVL. These include dysphagia, esophageal strictures, local ulcerations, and transient chest discomfort (13).

Band ligation is the cornerstone of the treatment of esophageal varices. Band ligation is one of the most commonly performed endoscopic procedures. Although variceal banding is mostly a safe procedure, it may be complicated by a serious adverse event. The preferred treatment for bleeding from esophageal varices, EVL is widely utilized in patients presenting clinically with this condition (14). In the present study, we aimed to determine the frequency of duodenal ulcer (DU), as well as other clinical characteristics occurring after endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) of the esophagus.

The current study was carried out on 240 subjects selected from the outpatients' clinic of the Internal Medicine Department of Monofia University Hospital and to Kafr El- Shiekh Liver Diseases Research Institute admitted to the internal department during period from Aug-2020 to June -2021. Divide into: Group 1: 120 patients having esophageal varices and were treated with band ligation, and Group 2: 120 patients having esophageal varices not receiving band ligation as a control group. According to demographic data of Studied patients; the mean± SD of age in the EVL group was 60.18±8.02 years and was 58.60±9.73 years in the control group, the majority of both groups were females as following in EVL group female 81(67.5%), male 39(32.5%) and control group female 69(57.5%), male 51(42.5%). There was no statistically significant difference between the control group and esophageal ligation group as regard age and sex. This comes in agreement with the study of Cho et al (15) found that the age of the enrolled patients was 59.5±11.1 years (range, 27–87 years). But regarding sex reported that the patients included 363 (84.4%) men and 67 (15.6%) women and this comes in disagreement with our findings. Also, Zhuang et al (16) reported that, the mean age of 51.3 ±11.5 years, ranging from 21 to 75 years. Disagreement with our findings regarding sex, the study of Zhuang et al (16) was aimed to determine the frequency of duodenal ulcer after esophageal varices ligation and reported that in the EVL group, male 36(76.6%), female 11(23.40%), and in the control group, male 44(73.3%), female 16(26.7%).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has designated the hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a serious health issue; as a result, HCV is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma, chronic liver disease, and liver-related fatalities as well as the most common reason for liver transplantation globally. One of the potentially fatal side effects of liver cell failure is portal hypertension-induced esophageal varices, which can cause a number of fatalities and comorbidities as well as negatively impact general health and liver transplantation readiness (17). According to the medical history of the studied patient and cause of cirrhosis: we reported the cause as follows, HCV (86.25%), bilharziasis (12.5%), and HBV (1.25%). There is no statistical significance difference between the control group and the esophageal ligation group. Disagreement with our finding, the study of Cho et al (15) reported that concerning causes related to cirrhosis, HBV 227(52.8%), alcohol 120(27%), HBV+ HCV 59(13.8%), and other 24(5.5%). Disagreement with our finding, the study of Zhuang et al (16) reported that the main cause of cirrhosis was HBV 94(87.8%) and other 13(12.2%). Additional research by Liaw et al (18) and Liu et al (19) examined the severity of liver damage in individuals with viral co-infection and those with single viral infection. In patients with viral co-infection, cirrhosis and liver injury are found to occur often. HCV-Ab was found in 10% of individuals with HBV-related cirrhosis; it was found in 8% of chronic HBV infections and increased with advanced liver disorders.

As regard laboratory findings among cases with EVL and control group, we found that there were non-statistically significant differences between the two groups as regards each of Hb, WBCs, platelets, AFP,creatinine, and Serum total bilirubin, INR, PT, and Albumin while there were high statistical significant differences between two groups as regards each of AST, ALT, and urea. This comes In agreement with the study of Zaghloul et al (20) aimed to evaluate the risk factors for predicting variceal bleeding after elective endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL).reported that there was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between both groups regarding ALT, AST, Albumin, total. Bilirubin, AKP, Hct, WBCs, ESR, S. creatinine, and Fasting Blood Sugar (FBS), but there was a statistically significant difference between both groups regarding prothrombin time (PT), Hb level, Platelet count (P<0.05). Disagreement with our findings, the study of Zhuang et al (16) Elhawari et al (21) reported that there was a statistically non-significant difference between all laboratory findings for EVL group and control group.

In the current study, the majority of cases in both case and control groups were in child Pugh B followed by score A and then C, (50%, 45%, 5% Vs 55%, 35%, 10% resp.) and as regard H. pylori; 20% of cases were positive and 80% were negative. In control; 25% were positive and 75% were negative. There was a statistically insignificant difference between the control group and esophageal varices ligation group according to child score and H pylori infection. In agreement with our findings, the study of Zhuang et al (16) reported that concerning Hp-infection status and child-pugh score, no difference was found between the EVL group and the control group .as following, respect to Hp infection, EVL group (19.1%, 9/47) and the control group (21.7%, 13/60, p=0.813), regard to child-pugh score, EVL group child A 15(31.9%), child B 23(48.9%), child C 9(19.2%) and control group, child A 23(38.3%), child B30(50.0%) and child C 7(11.7%). This comes in agreement with the study of Cho et al (15) regarding child-pugh score, the majority was child B 217(60.5%) followed by child A 146(34%) followed by child C 67(15.6%). This is in agreement with Madhotra et al (22) who found a significant relationship between the presence of varices and increased Child score. Thus, the more advanced the liver disease (according to Child classification), the more likely the presence of varices. Discussion patients with cirrhosis and Child C patients have the most advanced stage of liver cirrhosis with subsequent portal hypertension and the development of varices. Disagreement with our finding, the study of Zaghloul et al (20) aimed to evaluate the risk factors for predicting variceal bleeding after elective endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL). Reported that, there was a statistically significant difference between both groups regarding Child-Pugh classification (P<0.05). The bleeding patients had worse Child-Pugh scores, all were class C. On the other hand, 25.53% of non-bleeding were class A, 48.94% were class B, and 25.53% were class C (P-value=0.021).

On other hand, as regard comparison of Endoscopic PHG findings among studied groups at baseline; we found that majority of patients in both groups were of mild degree (37.5% vs 52.2%) PHG followed by moderate degree (30% vs 20%), and there was statistically insignificant difference between the control group and EVL group regarding portal hypertensive gastropathy grading. This comes In agreement with the study of Zaghloul et al (21) aimed to evaluate the risk factors for predicting variceal bleeding after elective endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL).reported that there was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between both groups regarding grading portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) as following in bleeding group, mild PHG 2(66.67%), sever PHG 1(33.33%) and in the nonbleeding group, none PHG 18(38.30%), mild PHG 14(29.79%) and sever PHG 4(8.51%). In agreement with our finding, the study of Zhuang et al (16) reported that there is no significant difference between EVL group and control group at baseline regarding PHG grading as follows, in EVL group, non or mild PHG 40(85.1%), moderate 4(8.5%), sever 3(6.4%) and in the control group, non or mild PHG 44(73.3%), moderate 12(20%) and sever 4(6.7%). Most studies of Abbasi et al (23) and Aoyama et al (24) showed that the frequency and severity of PHG is strongly correlated with the severity of portal hypertension, as indicated by multiple parameters, including hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), esophageal intravariceal pressure, and presence or size of esophageal varices.

In the present study, we found that there was a statistically significant between the control group and EVL group regarding esophageal varices grading (the majority were grade II 45% vs 50% resp.), PHG grading (the majority of EVL group were mild 32% vs moderate 40% in the control group), and duodenal ulcers (17.5% Vs 5% resp.) occurrence after 3 follow up. The range of occurrence of duodenal ulcers among EVL group after 3 months follow up was 21 patients (17.5%) with duodenal ulcers and 99 patients (82.5%) without duodenal ulcers. All the ulcers in EVL group were at the stage of (Forrest class III) with diameters ranging from 0.2 cm to 0.5 cm. In agreement with our findings, the study of Zhuang et al (16) reported that the incidence of DU in the control group was 6.7% (4/60), which did not differ statistically from the incidence in all patients receiving endoscopic examination during the same period (6.9%, 597/8652, p=1.00), In contrast, within the EVL group, 14 patients presented with DU (29.8%, 14/47), an incidence significantly higher than the control group (6.7%, 4/60, p=0.002). All the ulcers in EVL group were at A2 stage, with diameters ranging from 0.3 cm to 0.6 cm, and 7 of the 14 cases had mild epigastric pain. These 14 included 8 new cases of DU arising after EVL treatment, and 6 cases presenting with DU at the time of band ligation.

As regard comparison between PHG before and after esophageal variceal ligation; there was a statistically insignificant difference among EVL group regarding PHG grading before and after band ligation, the majority were mild (37.5% vs 32.5%). In agreement with our findings, the study of Zhuang et al (16) reported that within the EVL group, no significant difference was found concerning PHG grades before and after EVL treatment (p=0.470). In agreement with our findings, the study of Yoshikawa et al (25) reported that after EVL, only two patients (5.7%) developed severe PHG, 6 (17.1%) developed mild PHG, and 27 (77.1%) showed no change in endoscopic appearance of PHG. In those patients who developed PHG, EVL significantly decreased GMBF at the corpus (p < .05). However, no significant changes of GMBF at the corpus were noted after EVL in those patients who had no worsening endoscopic features. EVL did not affect GMBF at the antrum in any patients. Disagreement with our findings, the study of Noble et al (26) compared eighty-six endoscopies performed before ligation and 240 endoscopies performed after ligation. Before ligation, the prevalence of mild PHG was 47.67% and severe PHG was 17.44% [Global prevalence 65.11%]. After variceal ligation, mild PHG was 63.75% and severe PHG was 11.25% [Global 75%]. The impact of variceal ligation is more obvious for mild PHG. When subgroup analysis was performed in the post-ligation group according to the follow-up stage, the mild PHG increased from 47.67% (before ligation) to 64. 10% at two weeks, 62.3% at one month, 70.8% at three months, and 58.49% at six months.

In the study on our hands, as regard comparison of Endoscopic PHG findings before and after 3 months among control groups; there was a statistically high significant difference among the control group regarding PHG grading before and after 3 months follow up, the majority of the pre were mild (52.5%) and the majority of after was moderate (40%). In comparison with Tanoue et al (27) aimed to investigate the effect of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices on portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) two groups, PHG (+) (N=35) and PHG (-) (N=102) were distinguished by endoscopic findings obtained before EIS. PHG was classified into four grades by endoscopy scored as 0, 1, 2, or 3. The PHG score significantly worsened after EIS (p < 0.01), and PHG became worse 6 to 9 months after the eradication of varices followed by gradual improvement.

In the current study, there was a statistically insignificant difference among EVL group regarding relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcers. 25% of positive H. Pylori had duodenal ulcer and 15.6% of negative H. Pylori had duodenal ulcer. In agreement with our findings, the study of Zhuang et al (16) Hp infection rate in the 8 new cases of DU, arising after EVL treatment (12.5%, 1/8), was comparable to that in patients without DU in the EVL group (12.1%, 4/33, p=1.00). Hp infection was found in 3 of the other 6 patients with DU observed before EVL. In another study by Zhang et al (28) conducted in the same region as the present research, investigators have found that the prevalence of Hp infection was 51.4% - 59.4% in a population of people receiving gastroscopy, a result much higher than that of EVr patients in this study. Given that the aforementioned research discovered that Hp infection was most common in childhood, acquired by close contact with a carrier, the majority of Hp-infected individuals in that study appeared to be long-term carriers of the bacterium, beginning at an early age.

In the present study, there was a statistically significant Relation between duodenal ulcer and child scores among EVL group. There was a statistically high significant Relation between duodenal ulcer and PHG grading among EVL group. Disagreement with our findings, the study of Zhuang et al (16) reported that the incidence of DU occurrence in our EVL group was not correlated with age, gender, Child-Pugh classification, and PHG grades (p > 0.05).

In the present study, there was statistical high significant Relation between duodenal ulcers and the Number of ligation bands among EVL group. In agreement with our findings, the study of Zhuang et al (27)reported that the incidence of DU occurrence in our EVL group was related to the number of ligating bands introduced during EVL. Since there was a direct correlation between the number of ligating bands and the extent/severity of EVr, one can speculate that there may be a positive correlation between the number of ligating bands and the impact of EVL treatment on the hemodynamics of collateral circulation in patients with portal hypertension.

Reports on the effect of EVL on duodenal mucosa integrity have been rare. In this study, the incidence of DU increased significantly. This increase was, however, not related to Hp infection but rather to the use of a higher number of ligating bands. The authors of Oluyemi and Amole, (29) surmise that changes to collateral circulation during portal hypertension may be the key mechanism involved. For example, portal hypertension can induce dilatation of the vessels in the duodenal bulb, and EVL may exacerbate the high capacity and low perfusion of the duodenal bulb and injury to the bulb mucosa caused by hypoxia.

In conclusion, EVL increased the frequency of DU in EV patients, which was related to the number of ligating bands employed during EVL, but was not related to Hp infection. Moreover, more studies are required to elucidate the impacts of EVL on environmental changes within the stomach, as well as on the secretion of glucagon, gastrin, prostaglandin, vasoactive peptide, histamine, other gastrointestinal hormones, and gastric acid and pepsin. EVL may also impact abnormalities in gastrointestinal peristalsis and the longevity of exposure of the duodenum to injurious substances. In addition, whether sclerotherapy, an alternative procedure, may also provoke a high incidence of DU and should be investigated in patients with EV. Our limitation was the small sample size, therefore, the exact mechanism by which EVL increases the incidence of DU must be subjected to further investigation.

Conclusion

•EVL increased the frequency of (DU) duodenal ulcer in EV patients, which was related to the number of ligating bands employed during EVL, but was not related to Hp infection.

•The multivariate analysis demonstrates that there were four independent risk factors for duodenal ulcers are PHG, OVG III, EVL, and numbers of rubber bands.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Menoufia University faculty of Medicine's ethical committee.

References

1.Shaheen AA, Nguyen HH, Congly SE, Kaplan GG, Swain MG. Nationwide estimates and risk factors of hospital readmission in patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Liver International. 2019;39(5):878-84.

2.Yoon H, Shin HJ, Kim M-J, Han SJ, Koh H, Kim S, et al. Predicting gastroesophageal varices through spleen magnetic resonance elastography in pediatric liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(3):367-377.

3.Nery F, Correia S, Macedo C, Gandara J, Lopes V, Valadares D, et al. Nonselective beta-blockers and the risk of portal vein thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis: results of a prospective longitudinal study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(5):582-588.

4.Nigatu A, Yap JE, Chuy KL, Go B, Doukky R. Bleeding risk of transesophageal echocardiography in patients with esophageal varices. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32(5):674-676.e2.

5.Lahbabi M, Elyousfi M, Aqodad N, Elabkari M, Mellouki I, Ibrahimi SA, et al. Esophageal variceal ligation for hemostasis of acute variceal bleeding: efficacy and safety. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:95.

6.Dai C, Liu W-X, Jiang M, Sun M-J. Endoscopic variceal ligation compared with endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(8):2534-41.

7.Selmi S, Rtibi K, Grami D, Sebai H, Marzouki L. Protective effects of orange (Citrus sinensis L.) peel aqueous extract and hesperidin on oxidative stress and peptic ulcer induced by alcohol in the rat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):152.

8.Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(18):5191-204.

9.Luo JC, Leu HB, Hou MC, Huang CC, Lin HC, Lee FY, et al. Cirrhotic patients at increased risk of peptic ulcer bleeding: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 36(6):542-50.

10.Mahajan P, Chandail VS. Etiological and endoscopic profile of middle-aged and elderly patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a Tertiary Care Hospital in North India: A retrospective analysis. J Midlife Health. 2017;8(3):137-141.

11.Xu X, Jin Y, Lin Y, Hu D, Zhou Y, Li D, et al. Multimodal ultrasound model based on the left gastric vein in B-viral cirrhosis: noninvasive prediction of esophageal varices. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020; 11(11):e00262.

12.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W, Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases tPPCotACoG. Prevention and management of gastro-esophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-38.

13.Petrasch F, Grothaus J, Mössner J, Schiefke I, Hoffmeister A. Differences in bleeding behavior after endoscopic band ligation: a retrospective analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:5.

14.Jha AK, Dayal VM, Ahmed B, Kumar U, Kumar S. Variceal Banding: A Lesser-Known Complication. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016;6(1):77.

15.Cho E, Jun CH, Cho SB, Park CH, Kim HS, Choi SK, et al. Endoscopic variceal ligation-induced ulcer bleeding: What are the risk factors and treatment strategies? Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(24): e7157.

16.Zhuang Z-H, Lin A-F, Tang D-P, Wei J-J, Liu Z-J, Xin X-M, et al. Association of Endoscopic Esophageal Variceal Ligation with Duodenal Ulcer. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;26(4):267-71.

17.Abdel-Aty M, Fouad M, Sallam MM, Elgohary EA, Ismael A, Nawara A, et al. Incidence of HCV induced - Esophageal varices in Egypt: Valuable knowledge using data mining analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(4):e5647.

18.Liaw Y-F, Chen Y-C, Sheen I-S, Chien R-N, Yeh C-T, Chu C-M. Impact of acute hepatitis C virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):1024-9.

19.Liu CJ, Chuang WL, Lee CM, Yu ML, Lu SN, Wu SS, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for the treatment of dual chronic infection with hepatitis B and C viruses. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(2):496-504. e3.

20.Zaghloul SG, El Hady HA, Hussein HM, Hassan IA. Predictors of variceal bleeding after esophageal varices band ligation in egyptian cirrhotic patients. Zagazig University Medical Journal. 2018;24(1): 80-92.

21.Elhawari SA, Moustafa EA, Zaher T, Elsadek HM, Abd-Elazeim MA. Frequency and risk factors of post-banding ulcer bleeding following endoscopic variceal ligation in patients with liver cirrhosis. Afro-egyptian journal of Infectious and Endemic Diseases. 2019;9(4): 252-9.

22.Madhotra R, Mulcahy HE, Willner I, Reuben A. Prediction of esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34(1):81-5.

23.Abbasi A, Bhutto AR, Butt N, Munir S, Dhillo AK. Frequency of portal hypertensive gastropathy and its relationship with bio-chemical, hematological, and endoscopic features in cirrhosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011;21(12):723-6.

24.Aoyama T, Oka S, Aikata H, Nakano M, Watari I, Naeshiro N, et al. Small bowel abnormalities in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(5):1390-6.

25.Yoshikawa I, Murata I, Nakano S, Otsuki M. Effects of endoscopic variceal ligation on portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric mucosal blood flow. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(1):71-4.

26.Lugo AN, Vanegas GR, Acosta MEL, Rocha AG-A, de la Mora Levy G, Montemayor FJF, et al. Impact of variceal band ligation on the prevalence of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with esophageal varices. Anales Médicos de la Asociación Médica del Centro Médico ABC. 2002;47(4):202-5.

27.Tanoue K, Hashizume M, Wada H, Ohta M, Kitano S, Sugimachi K. Effects of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy on portal hypertensive gastropathy: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38(5): 582-5.

28.Zhang W, Hu F, Xiao S, Xu Z. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China. Modern digestion & intervention. 2010;15(5): 265-70.

29.Oluyemi A, Amole A. Portal hypertensive duodenopathy manifesting as "kissing" duodenal ulcers in a Nigerian with alcoholic cirrhosis: a case report and brief review of the literature. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:618729.

Full Text Sources:

Abstract:

Views: 2732

For Authors

Journal Subscriptions

Jun 2025

Supplements

Instructions for authors

Online submission

Contact

e-ISSN: 2601 - 1700 (online)

ISSN-L: 2559 - 723X

Journal Abbreviation: Surg. Gastroenterol. Oncol.

Surgery, Gastroenterology and Oncology (SGO) is indexed in:

- SCOPUS

- EBSCO

- DOI/Crossref

- Google Scholar

- SCImago

- Harvard Library

- Open Academic Journals Index (OAJI)

Surgery, Gastroenterology and Oncology (SGO) is an open-access, peer-reviewed online journal published by Celsius Publishing House. The journal allows readers to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full text of its articles.

Time to first editorial decision: 25 days

Rejection rate: 61%

CiteScore: 0.2

Meetings and Courses in 2025

Meetings and Courses in 2024

Meetings and Courses in 2023

Meetings and Courses in 2022

Meetings and Courses in 2021

Meetings and Courses in 2020

Meetings and Courses in 2019

Verona expert meeting 2019

Surgery, Gastroenterology and Oncology applies the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits readers to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, remix, adapt, build upon the published works non-commercially, and license the derivative works on different terms, provided the original material is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. Please see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Publisher’s Note:

The opinions, statements, and data contained in article are solely those of the authors and not of Surgery, Gastroenterology and Oncology journal or the editors. Publisher and the editors disclaim responsibility for any damage resulting from any ideas, instructions, methods, or products referred to in the content.

IASGO Society News

IASGO Society News